How I Cut 30k Words From My Novel (Without Killing My Darlings)

My 10-step process to trim down my manuscript before querying literary agents

When it comes to writing, I’m something of a maximalist. I enjoy visiting novels constructed of spare, minimalist sentences, all clean lines and uncluttered pages. But when I write, I tend to layer my words lavishly. Why use a single adjective when a three-word stack feels so luxurious?

Yet I know how annoying this can be from a reader’s perspective. And I’ve listened to enough episodes of The Shit No One Tells You About Writing podcast to understand that the word count of your manuscript matters; most agents won’t consider an adult novel over 100k words. Longer books are more expensive to produce, ship and purchase, which can make a hefty tome from a debut novelist less attractive to potential publishers.

By the time WE DON’T TALK ABOUT CAROL (coming June 3, 2025 from Bantam/Penguin Random House) was ready for beta readers, my manuscript had swollen to over 125k words. I begged my critique partners and book club friends for chapters, characters and subplots I could cut.

It was deeply validating that my intelligent and outspoken friends couldn’t suggest a major element of my novel to remove. But it also left me with an enormous challenge — how could I get my novel under 100k words without slicing substantial chunks?

Somehow though, I managed to do it. I trimmed more than 25k words before querying agents. By the time my agent was ready to submit my novel to editors, I’d cut over 30k words in total without stripping away any of my beloved characters, scenes or subplots. And my novel is so much better for it.

Even maximalists need to practice restraint. After all, it’s tougher to appreciate a gorgeous line when it’s buried beneath piles of unnecessary words.

While the process felt haphazard, meandering and occasionally hopeless at the time, I can now recognize the ten clear steps I took to make this significant cut possible, thanks to all of the invaluable advice I gathered along the way.

STEP 1: Don’t (Permanently) Delete Anything.

When you’ve spent weeks, months or years laboring over your manuscript, the idea of hacking away at your precious words can seem unfathomable. When it was time to start revising, I created a new copy of my manuscript, and saved the original draft for posterity/reference. This does wonders for the psyche; it’s much easier to make changes knowing your original is safe and whole, just in case.

I repeated this step every time I made a significant series of revisions. And when I reached the “Ruthless Edit” stage (more on that later), I pulled any larger chunk I removed into a document called “Misc. Cuts,” in case I regretted any of my decisions (spoiler alert: I didn’t).

STEP 2: Try Cutting the Total Percentage You Need to Cut From Each Chapter.

This was a brilliant tip I learned from author Courtney Maum, in response to a question I asked during a virtual retreat hosted by The Shit No One Tells You About Writing podcast. It’s a technique she used when she had to cut 20k words in a single weekend from a book she thought was perfect (my actual nightmare).

Since my novel was 125k words, I needed to cut at least 20% to reach the 100k mark before I began querying agents. So I made it my goal to reduce the word count of each chapter by 20%. Breaking the massive total goal into smaller chunks made the task feel much less daunting. But the question remained — what exactly should I cut?

STEP 3: Give Beat Sheets a Go.

I didn’t outline my novel in advance; I wasn’t even sure how the story was going to end until I was 75% through my first draft. At some point I received the advice to try creating “beat sheets,” going chapter by chapter and summarizing the key plot development/emotional change that occurred. This helps ensure that each chapter/beat moves the plot meaningfully forward, and spotlights weak chapters or repetitive beats, prime targets for cutting.

I highly recommend this exercise, whether you’re a plotter who tackles this before typing the first word in your manuscript, or you’re a pantser preparing to revise your first draft. Jessica Brody’s book Save the Cat! Writes a Novel does an excellent job of guiding this process; she also offers free beat sheets on her website.

It was illuminating to see my entire novel at a glance in 15 digital notecards, and compare its structure to many of the world’s most popular and renowned novels. Maddeningly, however, it didn’t reveal any unnecessary chapters or beats I could magically remove.

Someone suggested that I do the same thing for each scene within my novel, but I couldn’t bring myself to do it. It would take forever! I’d have to fill out a zillion notecards!

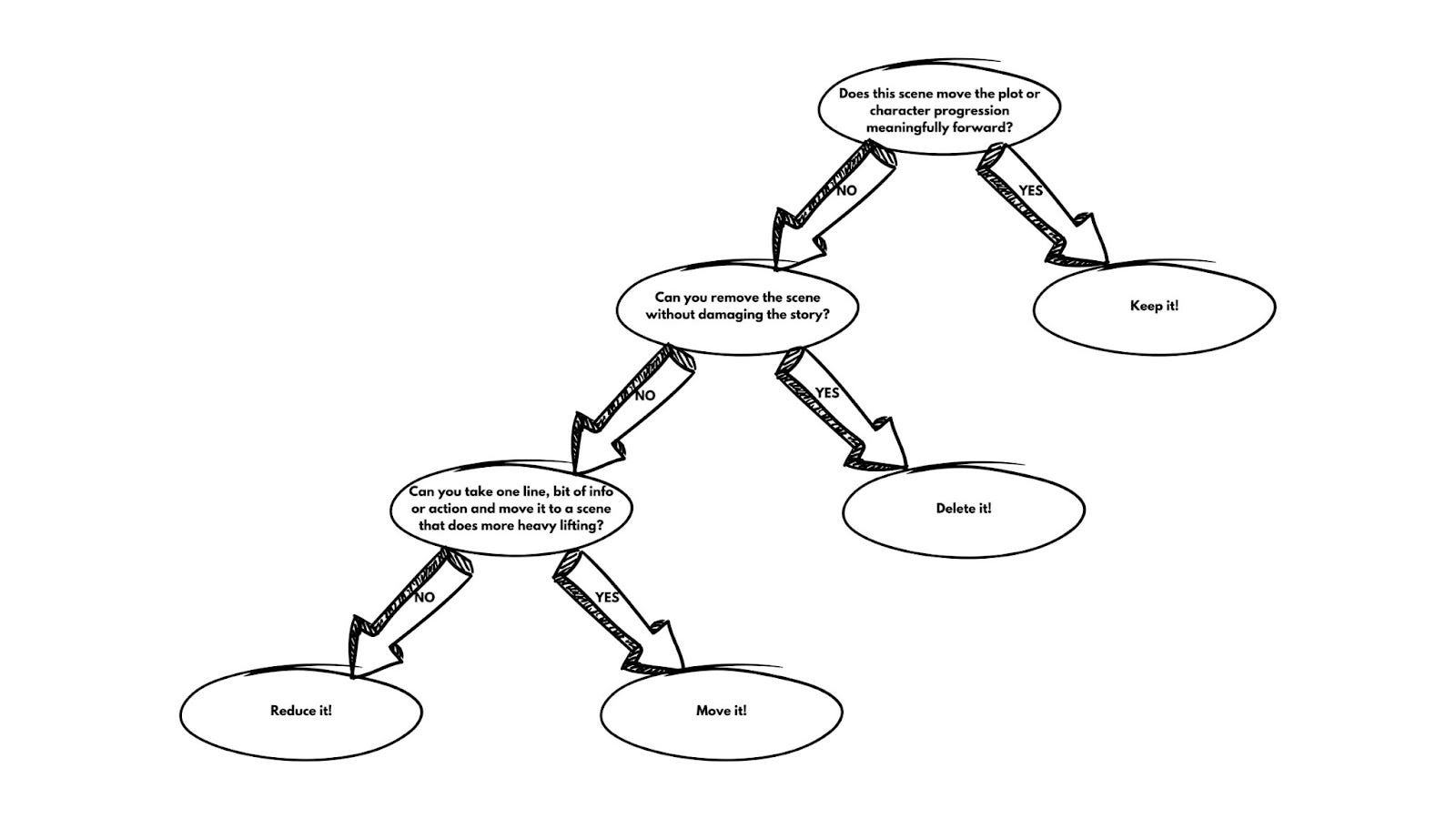

Instead, I carefully read each scene and asked myself the following questions:

Which leads to the next lesson I learned…

STEP 4: Not Everything Needs to be Conveyed In-Scene.

This is a tricky concept if you, like me, have deeply internalized the writing advice “Show, Don’t Tell.” However, “showing” everything can lead to a bloated manuscript, and can distract your reader from the scenes that matter most. So how do you know what to show vs. tell?

I love this explanation from author Shauna Grimes: “Showing is taking a friend to a party with you. Telling is texting them the juicy details in the morning.”

Ask yourself the questions outlined in Step Three. If a scene doesn’t push your plot or character progression meaningfully forward, but it provides the reader with an important piece of information, you can probably find a way to summarize that information.

For instance, my main character has a few pivotal, heated conversations with her husband in my novel. The heat often comes in response to his learning something my main character has done/plans to do that he vehemently disagrees with. Instead of showing her catching her husband up on something the reader already witnessed firsthand, I tried to summarize what she shared with him in a single line without repeating the information in detail.

This resource from Grand Valley State University is also helpful if you’d like to dig into the topic of showing vs. telling further (they offer numerous resources from their Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors, here).

STEP 5: Consider Combining Characters.

Early on in my revision process, author Diane Marie Brown posted on Instagram recommending a workshop all about novel revision. Diane’s post felt like divine intervention. I’d felt completely lost in the vast woods of my manuscript, and author Elana K. Arnold’s Revision Season workshop provided me with a detailed map leading me out of the forest.

Instead of insisting on hard and fast rules, Elana asked thoughtful questions and encouraged us to consider if they rang true for us. One such question was whether each of my tertiary characters fulfilled more than one job, and if they didn’t, could I combine them?

My main character met numerous people during her investigation of her aunt’s disappearance. I listed them all, and considered the role each played in my story. I was able to remove a few tertiary characters and their minor scenes via this approach. For example, if the character’s role was simply to provide my protagonist and the reader with key information, and the character only popped up once, I found ways of supplying the information via a different character with a more prominent role, or by summarizing an article found or a conversation had without illustrating it in-scene.

STEP 6: Excise Overused/Filler Words.

In his brilliant craft book Refuse to be Done, author Matt Bell discusses the concept of “weasel words” — commonly used empty descriptors that can/should be deleted or replaced by a stronger, more precise word.

When I read that he deleted eight hundred uses of the word “that” from one of his novels, I knew I had to give this technique a try. Helpfully, Matt included several examples of filler words in his book to get me started (I was horrified to learn I’d used 637 instances of “like”).

I deleted a few thousand words through this method. It also trained me to edit more closely on the line level. I quickly realized how rarely I needed dialogue tags other than “said,” and how frequently I could remove the adverbs I used alongside these words.

I recalled Elana’s urging that when revising, every word should fight for space on the page; removing the word would take something important away. I needed to zoom way in, beyond the story, and take a scalpel to every word I could bear to spare. I needed to become ruthless.

STEP 7: Do a “Ruthless Edit.”

During another virtual retreat led by The Shit No One Tells You About Writing podcast, I asked co-host and literary agent CeCe Lyra for her advice on substantially cutting down a novel’s word count. Among her helpful advice was the admonition to be ruthless in my editing. To pretend that I’m a different person than the author.

I took CeCe’s advice to heart. I printed my manuscript, took out my red pen, and vowed to read my novel not as the author, but as an editor. An editor whose primary task was to ensure that every word was vital to the story.

Creating emotional distance by taking on the persona of an editor was immensely useful. As was the physical distance of stepping away from my screen, where the temptation to immediately tweak/rewrite is too strong.

You can take this a step further by bringing your manuscript to your favorite coffee shop, park or beach, anywhere you might read for pleasure. Or try reading it aloud, cosplaying as your future audiobook narrator (I cut many words this way). If you can, give yourself some time (days, weeks, months) between your latest revision and the “Ruthless Edit” stage. It’s amazing what will jump out at you when you’re able to review your work with fresher eyes.

STEP 8: If Using First Person, Employ Narration Sparingly.

I didn’t realize I did this until my literary agent, the brilliant and wise Sharon Pelletier, pointed it out in her first round of feedback for CAROL. When you’re writing in first-person perspective, it’s up to your main character to vividly paint their world for your reader. However, if, let’s say, your main character is in a heated argument with their partner in a restaurant, they’re probably not focusing much on what the room looks like, or what the servers are up to; they’re concentrating on the conversation, how it’s making them feel, and the implications the conversation may have on their future with their partner.

I read my manuscript again with this feedback in mind, and found I was able to cut way back on narrative description in key scenes while still providing a clear picture of setting. As Sharon expected, these tweaks helped tighten the pacing of my novel.

STEP 9: Pare Down Long Emotional Conversations Whenever Possible.

This was another bit of sage advice Sharon offered. My novel is as much a family drama as it is a tale of suspense, and there are numerous emotionally-fraught conversations throughout the book. Yet even if a conversation is deeply intense, it doesn’t hold a reader’s attention as strongly as action.

While these conversations are a crucial element of my novel, it was important that I kept them as tight as possible, looking for “any additional opportunities to pare without lessening their impact or the content you want them to communicate,” as Sharon suggested.

In addition to cutting back unnecessary narration, I removed lines that repeated points made elsewhere in the novel, pushed myself to excise as many words as I could, and tallied how often I used certain reaction descriptors (my main character’s “stomach twisted” way too many times).

On future re-reads, I was shocked to find that I didn’t miss the words I’d cut. It was as if they never existed at all.

STEP 10: If You Can, Give Your Manuscript — And Yourself — Room to Breathe.

It took me ~21 months to write the first draft of CAROL, ~16 months to revise it before querying, and ~1 month of revisions with my agent before the book was ready for submission to editors. And a significant chunk of my revision time was spent trimming down the word count/improving the pacing of my novel.

I may not have the same luxury of time when I’m next faced with this task (my next novel is due to my editor in July, after all!). But as much as possible, I’ll try not to force or rush my way through this process.

Trimming a novel is like cutting back an overgrown shrub. By clearing away the weaker, overcrowded bits that are no longer useful to the plant, you help the healthy branches thrive. However, if you hack away at your plant indiscriminately, you might inadvertently sever a crucial limb, or kill the shrub altogether.

By taking time to sit with each of these questions, and giving myself a break (when possible) between revision steps, I was able to more clearly see what needed to be cut. Tackling my revision in a series of passes, with each pass focusing on a different element — eliminating plot holes, deepening characters, re-evaluating long emotional conversations — also helped create the illusion of distance, by focusing on pieces instead of the novel as a whole.

It’s tempting to look at those 30,000 deleted words and think, wow, what a colossal waste of time. Instead, my agent Sharon referred to these words as “scaffolding,” and I think this is a perfect analogy. The temporary structures surrounding buildings under construction are there to provide extra support for the people putting the building together. As an author feeling your way through a story, learning the core of your characters as you go, it can be tremendously helpful to write every emotion, every setting, every memory, and every conversation in vivid detail. It’s during the revision process that you can begin to strip away those extra layers, giving your reader’s imagination space to fill in the details, and trusting them to analyze and understand what they’ve read without telling them what to feel, think or notice.

While I hope some of these lessons stick with me during my writing process, I’m not pressuring myself to employ them all while drafting my new manuscript. If anything, I can relish penning the first draft as my naturally maximalistic self more than ever, knowing I now have a ruthless, minimalist editor that lives within me, ready for me to tap her skills when it’s time.

Thank you so much for reading! Have a topic you’d like me to cover in a future post? Drop me a line here.

This is THE post I needed!! So many amazing nuggets and I love the 'scaffolding' analogy!

This is so helpful and instructive, thank you! I wrote my first novel for NaNoWriMo and got to 53,000 words by November 30. It's now at 65,000 and it's done - well, the first and second draft. I'm going to serialise it right here on Substack soon, but I still have plenty of editing to do. I only recently read Save the Cat! so I will play around with those beat sheets as well.